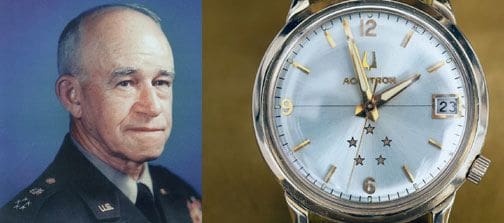

Omar Bradley and his Accutron

I was fortunate enough to repair a similar Accutron 218, obviously once owned by Omar Bradley due to the insignia on the backside, and I suspect it was given by him to someone.

Bradley was the last U.S. officer to hold a five star rank, which denotes a General of the Army. Bradley was instrumental in running Bulova, but he was also committed to the rehabilitation of U.S. military veterans into society, training former soldiers at Bulova’s watchmaking school, and using Bulova’s program as a blueprint for retraining soldiers after their military service. He also helped Bulova become not only a watchmaking company, but a maker of critical timing instruments for military and aerospace applications, especially during the Cold War.

Bradley became the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff but retired from active service in 1953 having become disillusioned with the Truman administration’s handling of the Korean War.

It seems natural in hindsight that as an officer concerned with the welfare of soldiers, that Bradley became head of the Veteran’s Administration, a position he held from mid-1945 to 1947. He was particularly interested in helping wounded veterans ease back into civilian life. The Bulova School of Watchmaking was of interest to him from the outset, as the School was a pioneer in accessibility for the disabled, and was designed to help make disabled servicemen feel at no disadvantage. Graduates could be sure of employment with over 1500 positions pledged by the Jewelers of America.

Omar Bradley became Chairman of the Board for the Bulova Watch Company from 1958 to 1973. It was a time when the watchmaking industry in the U.S. was increasingly seen as a vital element not just in consumer products, but in the American defense industry as well.

Bulova hired many servicemen to work in their factory at the time.

Watchmaking was so important to the U.S. in terms of essential skills and technology that in July, 1954, President Eisenhower increased the tariff on imported watches “… to aid the security of the United States by insuring the preservation of essential skills…” This decision rested on the recognition “… that the American watchmaking industry is essential to our national defense …” (Bulova Watch Company Annual Report, 1955). Mr. Arde Bulova was called upon to speak before a sub-committee for the Committee on Armed Forces of the United States in which he detailed the critical role of watchmaking and the manufacture of precision devices for weapons supplied to the Army, Air Force, and Navy.

Not only was Bradley Chairman of the Board, he was also (and this is less well known) Chairman of Bulova’s Research and Development division from 1954 onwards.

In this capacity Bradley made a telling case (in Bulova’s 1955 Annual Report) as to why President Eisenhower had signed off on the increase in the tariff. Uppermost in Bradley’s mind was not only the supply of precision parts and instruments, but also the skilled labour required to manufacture and maintain such precision devices. As Bulova had manufacturing facilities in both the U.S. and Switzerland, it was uniquely placed to benefit from technology and production in both locations without incurring the tariffs on their products. However, the concern was to retain domestic production and supply. The lessons learned from the Second World War and the Korean War were still very much in Bradley’s mind. He wrote letters to Bulova’s shareholders assuring them that the protectionist measures were in the national interest for defense.

Under Bradley the R&D department began producing timers, and also many other precision devices, for military applications; in 1954 he wrote, “Bulova is producing mechanisms of the most complex and delicate nature for our national arsenal – detection devices for guided missiles, mortar fuzes, mine detectors, complicated torpedo-head assemblies, quartz crystals, and certain devices which are classified as secret by the Department of Defense.” In just one year (1954) the number of employees at the Research and Development division increased fivefold. And a critical element, for both consumers as well as for the military, was the development of the watch known as the Accutron.

In 1952 Bulova’s Harry Henshel went to Switzerland to research possible new technologies for watchmaking, having become concerned about advances in electronic watches by rivals like Elgin and Lip. There he met engineer Max Hetzel at the Bulova factory in Bienne. It was Hetzel who became the father of the Accutron tuning fork watch and by 1954 he had already made a working prototype. The 1958 Bulova Annual Report said, “This timepiece will for the first time harness electronics to produce accuracy surpassing that of any mechanically energized watch.” The Accutron movement was built around a low voltage Raytheon CK 722 transistor and unlike Bulova’s rivals’ electronic watches, used a vibrating tuning fork rather than an electrically impulsed balance wheel.

The very first Accutron movement, the 214, was inside the first Accutron watch sold in 1960 and Accutron technology quickly became the standard for high precision timekeeping – both on the wrist, and in military, aerospace, and navigation applications. Accutron came to define the company. 46 NASA missions were flown with Accutron clocks in the cockpit. In 1964 President Lyndon Johnson gave Accutron clocks to visiting state dignitaries. Air Force One was equipped with Accutron clocks and NASA even left Accutron timers behind on the Moon as part of lunar experiment packages.

Accutron and Bulova became synonymous and even today the watch many think of when they hear the name Bulova, is the Accutron. Bradley’s Bulova Accutron, which was located recently in a private collection, is very in keeping with watch design in the latter part of the 1960s, with a Calatrava style watch case and crown offset at 4:00. The silvered satin finished dial and gold markers are also typical for the era.

What sets this apart as one of Bradley’s watches is the five star insignia. These were actually a series of watches that were given as gifts by the company, and Bradley would actually wear the watch daily until it was given as a gift. This was not an everyday occurrence of course and the Bulova Museum believes that no more than 12 were made, so this is likely one of 12; the current owner declined for now to let the Museum acquire this example as it’s a family heirloom.

His watch is an Accutron 218, made around 1968, and it symbolizes a time when American watchmaking not only produced technical marvels (albeit in Switzerland) but also provided mechanisms and material essential to US defense. By the time Omar Bradley stepped down as Chairman, in 1973, Bulova had sold around 4 million Accutrons, providing an unprecedented level of precision.

The movement of the Omar Bradley 5 star Accutron; at the top are the two heads of the tuning fork and the driving coils. The two copper colored circles inside the triangular cut-out of the bridge are the attachment points for the arms holding the index jewel, and the pawl jewel.

An interesting aside in the story (and there is some contention in literature dealing with the sequence of events) is that Hetzel almost left Bulova for Omega in 1957. Hetzel’s first prototype, though granted a patent, was not reliable and the manager of the Bienne factory wanted to scrap it, so Hetzel threatened to leave. Arde Bulova personally intervened and offered Hetzel the position of chief physicist at Bulova’s New York plant, and it was there, in 1959, that prototypes of the first successful production models were produced.

Just a year after this watch was made, Seiko sold the first commercially viable wristwatch with a quartz movement: the Astron. The era of Accutron as the world’s most accurate production watch was drawing to a close. With the waning of General Bradley’s influence and the loss of his connections to the corridors of power in Washington, Bulova’s place in the military supply chain also came to a close. This “Five Star” Bulova Accutron 218 is symbolic of both the pinnacle, and the beginning of the end, of an amazing chapter in American watchmaking history.

Tags: